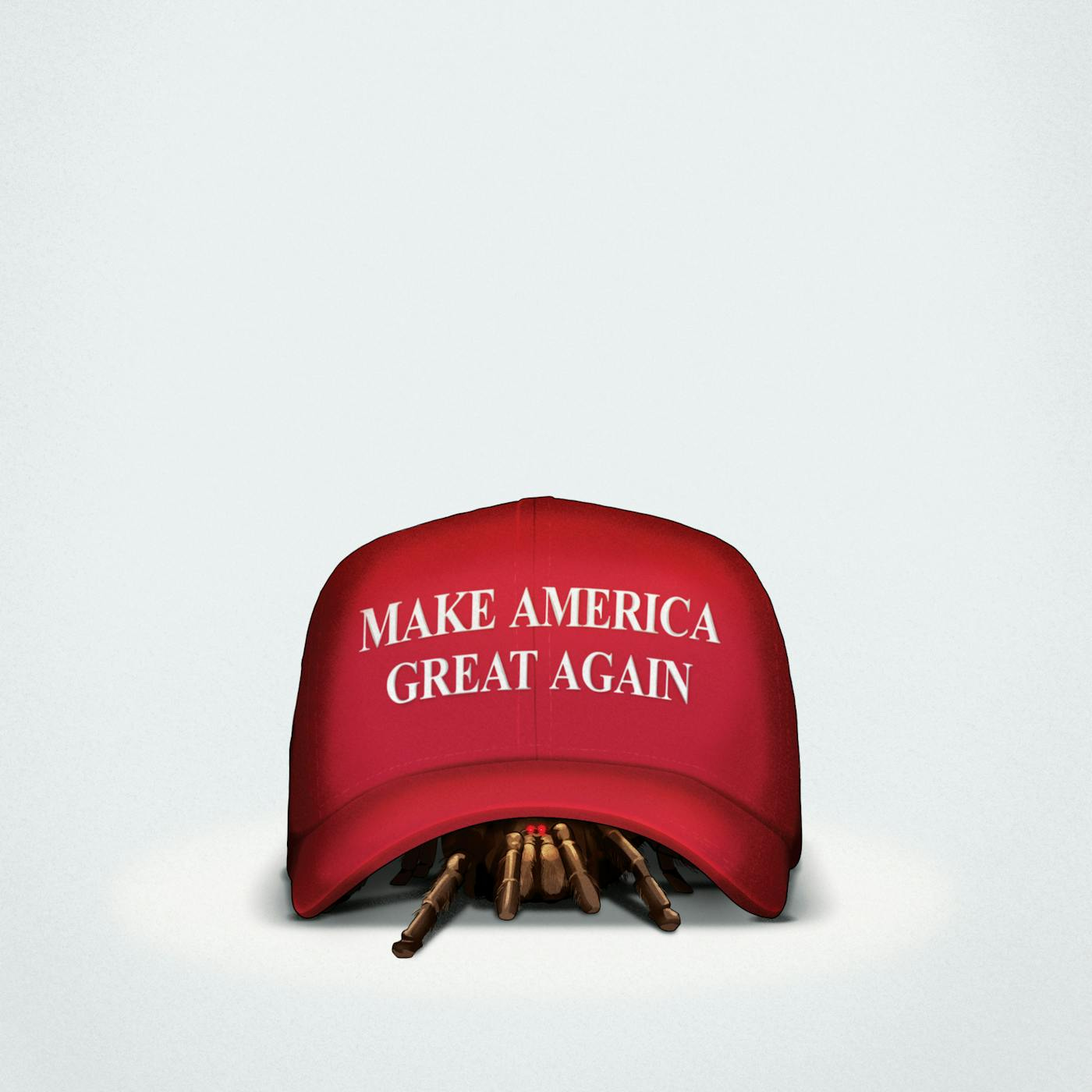

Trump’s Slow-Burn Authoritarianism

A legal war of attrition that harasses MAGA’s enemies and transforms government info into propaganda could prove more insidious and harder to mobilize against.

by Greg Sargent

If Donald Trump wins in November and launches a full-blown authoritarian presidency next year—as he has promised to do in his own words—what exactly would that national nightmare look like?

One set of oft-floated worst-case scenarios looks something like this: Trump orders his pliant pick for attorney general to prosecute Liz Cheney and other high-profile critics and frog-march them before the cameras. Trump invokes the Insurrection Act to dispatch the military into cities to crush mass protests. Trump unshackles deportation forces to drag millions of undocumented immigrants from homes and workplaces. Trump purges our nation’s intelligence services, stocks them with loyal foot soldiers, and unleashes them as a domestic spying force to gather information on designated enemies of the MAGA movement.

It would be folly to dismiss these possibilities, since Trump has repeatedly threatened to carry out something resembling every one of those things. He has vowed to prosecute his political opponents without cause. He has loudly called for the indictment of members of the congressional committee that investigated his January 6, 2021, insurrection attempt. He has mused aloud that he might send the military into Democratic-run cities. Trump and his advisers have floated plans for mass migrant removals facilitated by huge detention complexes and even potentially carried out by the military. Trump has repeatedly pledged to purge the supposedly corrupt “deep state”—his shorthand for federal law enforcement and intelligence services—and has openly suggested he would use state power to persecute domestic enemies he describes as “vermin.”

Yet as horrifying as all that is, another, less-garish scenario also potentially looms—and in some respects it might be a more plausible one. A second Trump presidency could unleash a kind of lower-profile, slow-burn authoritarianism, something that unfolds much more quietly and largely behind the scenes. In its targeting of internal enemies and its efforts to carry out revolutionary changes via far-right governance, it could end up being much less dramatic, visible, or splashy—but at the same time, extremely insidious, difficult to track, and very challenging to mobilize against.

The potential victims of such behind-the-scenes actions grasp this possibility perfectly well. While we constantly hear about high-profile preparations by Democratic lawmakers, pro-democracy advocates, and other interested stakeholders against the most nightmarish authoritarian scenarios underway, another more subterranean layer of preparations is quietly unfolding among a different class of targets.

These are Trump critics who have already hired lawyers who are advising them to gird for low-grade bureaucratic bullying. They are advocates anticipating years of legal warfare against vulnerable populations like transgender Americans. They are state-level officials scouring statutes to prepare for legal tussles over who controls the National Guard. They are career government officials bracing for the corruption of official information to serve the autocrat in chief’s whims and propagandistic needs, and the underhanded subversion of rulemaking processes to deliver spoils to his cronies. In interviews, what people in these situations say they anticipate is a type of legal and bureaucratic uncertainty that isn’t anything like watching troops invade cities—but nonetheless could prove highly unpredictable and deeply, unsettlingly precarious.

“We are organizing to win this election, but if, God forbid, an authoritarian MAGA clampdown comes, it may not be tanks in the streets and midnight disappearances,” Democratic Representative Jamie Raskin of Maryland told me. “It may be more akin to a corrosive long-term campaign of constant official and vigilante harassment against perceived political adversaries of the president-king.”

“Either Way, the Targets Would Be in Hell”

Again and again, Trump and his allies have declared right in the open that a second Trump presidency will unleash law enforcement to carry out mass persecution of MAGA’s designated enemies.

“We will go out and find the conspirators, not just in government but in the media,” Kash Patel, a high-level national security official during Trump’s first term who is expected to play a senior role in a second one, enthused last December. “We’re going to come after you.” Longtime Trump loyalist Steve Bannon has similarly suggested that, in Trump’s “first couple of months,” prosecutions will “get rolling.” People credibly being floated for high-level Justice Department positions—such as right-wing lawyer Mike Davis—are openly threatening such campaigns. Longtime Trump adviser Stephen Miller has called for Trump-friendly U.S. attorneys to prepare in advance to prosecute Democrats based on nothing more than the big lie that current prosecutions of Trump are illegitimate.

These exchanges were quietly and widely noted by a very particular class of people: high-profile Trump critics now bracing to be victimized. Tellingly, however, what these people are actually envisioning is not quite what all these Trump allies are threatening. While they do believe Trump and his allies will attempt splashy prosecutions, they expect something more like sustained legal and bureaucratic harassment.

Mark Zaid, a veteran lawyer in Washington who represents federal employees and intelligence officials, said he now has at least a dozen clients who are actively planning for years of exactly that. He has advised them to expect Justice Department investigations that might not lead to prosecutions but nonetheless would drain them of resources; IRS investigations into their taxes and business ventures; revoked passports; or threats to cancel security clearances—all designed to get potential critics to self-silence.

“A second Trump administration will not hesitate to exercise every executive branch weapon it can against those it considers enemies, real or otherwise,” Zaid told me. “We expect a very targeted approach designed to drain the financial resources of perceived adversaries, designed to leave them neutralized and isolated.”

What might such an effort look like? After talking to a number of people preparing for such eventualities, I can report that they’re largely bracing for something like this: In early 2025, an emboldened President Trump orders his attorney general to drop ongoing federal prosecutions of him over his insurrection and theft of state secrets. As the public debate over this unfolds on the airwaves, Trump gets particularly irritated by commentary from, say, a longtime critic who is now castigating his latest moves. Perhaps that person is a commentator (George Conway) or someone who investigated Trump during his presidency (Andrew Weissmann, a top official in the probe of Russian interference in the 2016 election), or a member of the January 6 committee (Liz Cheney). Trump curses uncontrollably about that person in a private conversation with his attorney general, and offhandedly mentions hearing that he or she is up to unsavory activities related to his or her business or legal practice.

But—unlike in the nightmare scenarios we’ve heard—this never results in real prosecutions. Instead, word of Trump’s rage filters down the chain of command in the Justice Department until it lands in the lap of an FBI agent or U.S. attorney who is eager to stand out to Trump and his top advisers. An investigation ensues. Investigators start calling that person’s associates and dig through his or her records. Nothing more materializes, but it puts the target through months or years of deeply unsettling, and expensive, precarity.

“That’s a completely plausible scenario,” Peter Keisler, who held high-level positions in the Justice Department during the George W. Bush administration, told me. Keisler said Trump would likely choose his attorney general precisely because he’d willingly transmit Trump’s whims to eager subordinates. Alternatively, Keisler said, Trump’s White House chief of staff could well be a loyalist willing to ring up a Trumpy U.S. attorney and make a suggestion or two about someone who has displeased Trump.

Perhaps this will strike readers as overly speculative. But it shouldn’t. Trump already tried to order prosecutions of foes during his first term. And if anything, the expectation of harassing investigations—ones that fall short of prosecutions—is a benign way to interpret the second-term intentions that Trump and his allies have openly articulated. Preparations for this are grounded in a basic recognition about the justice system: Trump and his allies probably won’t be able to launch baseless prosecutions on a mere Trumpian whim—that would require the cooperation of grand juries and courts. But they probably can create lots of hardship just short of that.

“The first steps of any investigation are very easy to initiate—much easier than prosecutions are,” Keisler said. “Preliminary investigations face far fewer checks or interventions by independent actors in the system, like judges. And they can do a lot to ruin people’s lives. Either way, the targets would be in hell. The question is just which circle of hell they’d be in.”

Along these lines, Zaid has been advising clients who are high-profile critics of Trump to prepare for IRS audits directed at their personal finances or organizations they work for—such as nonprofits or political action committees—and efforts to target such groups’ tax-exempt status. Intriguingly, in prepping clients for the threat of revoked passports, Zaid has been examining the long-forgotten case of a CIA officer named Philip Agee, who soured on the CIA’s methods and was accused of working for rival intelligence services. Agee had his passport revoked on national security grounds by the State Department under President Ronald Reagan, and Agee fought it all the way to the Supreme Court, but lost.

Agee’s case is a potential model for the present, Zaid said. That’s because the executive branch and hyperpoliticized agency heads have endless tools to exert abusive pressure on high-level bureaucrats, based on flimsy national security rationales. “Termination of employment and revocation of security clearances on national security grounds are very difficult to legally challenge even under current law,” Zaid said. “It would not take much to abuse the current system in an incredibly devastating way.”

One client of Zaid’s who fears retribution is Olivia Troye, a longtime Republican and senior Homeland Security official in the first Trump administration. She became a prominent critic of Trump, and since then Trump allies have targeted her with public calls for retribution. Troye fears revocation of her passport and national security clearance (and those of her husband, who works for the government), as a means of sending a warning to other would-be Trump critics—and she is making contingency plans to move abroad if necessary. “Nothing is off the table for what they could do to me,” Troye told me. “I’m looking at other countries where I could potentially reside.”

Perhaps you don’t have much sympathy for Republican former national security officials. Even so, it should be self-evident that the use of state power against them to suppress their informed dissent—and to frighten others into muzzling themselves—is something we should strenuously resist.

An instructive case here is that of Marc Polymeropoulos, a former CIA officer who has been in the crosshairs of Trump loyalists ever since he signed a letter in 2020, with other intelligence professionals, warning that stories about Joe Biden’s son Hunter Biden might reflect Russian disinformation. The letter didn’t say this definitively; it merely warned of it. Though some aspects of the Hunter Biden tales turned out to be true, the letter was partly vindicated when news emerged that an FBI informant charged with telling the bureau lies about the Bidens had been in touch with Russian intelligence, and it was a reasonable stance given what was known at the time. Yet Trump has actively accused its signatories of “treason,” an extraordinary, if implicit, threat of retribution.

Polymeropoulos has already had an experience that hints at where all these threats might go next. He recently learned that a class on the CIA presence in Afghanistan that he’d contracted to teach this fall at the Citadel, a military college in South Carolina, was canceled, according to Zaid, who is his lawyer. This came after school administrators privately told Polymeropoulos that prominent alumni pressured the administrators to nix his teaching gig because of that letter and his other public opposition to Trump, Zaid said. “I was canceled from the right,” Polymeropoulos said. “It was tremendously disappointing for me.” (A statement from the Citadel says the class was merely moved from the fall to the spring. Polymeropoulos dismisses this, insisting the effect was nonetheless that a class he’d hoped to teach was nixed, seemingly due to criticism of Trump.)

It’s easy to see how this could get much worse—and become a model to suppress dissent—during a second Trump administration. Trump allies or advisers could plausibly indicate to big institutions desiring to remain in good favor with Trump—conservative-leaning universities, nonprofits, media companies—that they should think hard before keeping this or that offending Trump critic in their employ. They might err on the side of caution and remove the objectionable figure. Alternatively, people might self-censor to avoid such punishment, knowing that institutions are under intense MAGA pressure to police them.

“Institutions will worry about retribution from Trump and his allies,” Polymeropoulos said. “And that will have a chilling effect.”

Against Immigrants, a War of Attrition

This discussion of the lower-grade authoritarian menace posed by Trump is in no way intended to downplay the seriousness of his most incendiary threats. Take Trump’s talk of deploying the National Guard to help carry out mass deportations. Democrats are actively preparing for this in unappreciated ways.

In a recent interview, Trump suggested he’d do this in places he deemed subject to “invasion” by undocumented immigrants—that is, in places where they live, work, pray, raise families, and populate communities—including in blue states that oppose the move. When asked whether he’d really target civilians this way—which would be illegal under federal law—Trump shrugged that migrants “aren’t civilians,” suggesting he’d deploy the National Guard to treat them as members of a hostile invading army.

As fanciful as that sounds, not only is it exactly what Trump is publicly threatening to do, but Stephen Miller—who visibly relishes elaborating on his sadistic fantasies—is treating this idea with the utmost seriousness as well. Miller has even fashioned concrete plans to carry it out. Because many migrants reside in blue states, Miller has suggested that friendly GOP governors not only should activate their National Guards to remove migrants from their own states, but also should cross into blue states and conduct such operations there.

That would almost certainly get blocked in court, as Ronald Brownstein persuasively explains in The Atlantic. But if Trump wanted to take charge of National Guards in blue states—as he has telegraphed—he could do so legally under various federal statutes. The question is what he could lawfully carry out with them, and it’s here that the preparations of blue-state law officials enter the picture.

“A president can take control of a state’s National Guard, even without the state governor’s consent,” said Joseph Nunn, counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice. “If the president then directed those troops to carry out mass deportations, the state could argue that it violates federal laws against using the military for domestic civilian law enforcement.” Nunn added that, if the president invokes the Insurrection Act in the process—vastly expanding the scope of what he could command National Guards to do—it would be harder to challenge, though such a challenge still might be doable if the order otherwise violates federal laws or the Constitution.

In short, it’s clearly a live possibility that Trump might try to issue an illegal order to blue-state National Guards. And as it turns out, some state attorneys general agree. In an interview, New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin, a Democrat, suggested that he and other attorneys general are preparing for showdowns over such Trumpian moves, and are ready to resist any potential illegal orders from Trump. “Any effort to unlawfully direct our National Guard or law enforcement more broadly would be met with heavy resistance from attorneys general,” Platkin told me. “We will be prepared for that.”

Immigration lawyers also expect a new push to enable states to deny free public school education to undocumented immigrant kids. This would require overturning a

Corrupting the “Deep State” to Enrich Trump’s Cronies

That sort of deep corruption of government information would pose a threat under an authoritarian Trump presidency that goes far beyond immigration. That’s due to an unappreciated aspect of his intention to purge the “deep state” and replace untold numbers of federal employees with MAGA loyalists.

Trump, who regularly rails against the “deep state,” has privately told advisers he’s planning to fire far more than the 4,000 or so federal employees who typically turn over from one administration to the next, according to Jonathan Swan and Maggie Haberman of The New York Times. As has been widely reported, an executive order creating a new “Schedule F” category for federal government workers—which Trump tried to do in his first term—would potentially subject tens of thousands of employees to replacement.

Many analysts have said that this would comprehensively wreck the professionalism of the federal bureaucracy. But there’s another, less-remarked-upon danger here as well: a corruption of government information that could leave the public awash in propaganda and make it easier for Trump’s corporate cronies to hijack the rulemaking and governing process for personal gain.

A concrete example suggested to me by a senior Department of Labor official illustrates the point. In July, the Biden administration proposed a regulation that would institute a federal safety standard protecting millions of workers (many of whom work outdoors) from excessive heat, amid rising heat-related fatalities. The proposal—which is opposed by some big-business interests—is now in an extended notice-and-comment period, and if Trump wins the election, the rule’s fate would be in the hands of his new administration.

It’s easy to see what might happen next. As the Labor Department official said, loyalists installed in key positions could easily ensure that quality science on the impact of heat on workers is ignored or downplayed during later stages of the rulemaking process. Meanwhile, career government officials—suddenly more vulnerable to firing—would surely hesitate to challenge or expose political appointees who are manipulating the process. “All he has to do is put the right people in the right jobs, and he can kneecap whole federal agencies,” the Labor Department official told me. “Science and evidence-based information driving government decisions will be completely thrown out the window.”

Once again, this is not theoretical: During Trump’s first presidency, Stephen Miller actively suppressed government data finding that refugees confer economic benefits on the country. Under a Trump administration with far more loyalists in key positions, such things could very well become the norm—and get executed far more effectively.

Here again, something short of the most dramatic scenarios—mass firings and the wholesale stocking of agencies with hundreds of slavish MAGA devotees—might end up happening. Instead, we’d see strategic firings and efforts to corrupt governing processes bureaucratically and behind the scenes. “It would not take the firing of that many officials to lead to the systematic suppression of scientific information in the rulemaking process,” Donald Moynihan, a professor of public policy at the University of Michigan, told me. “In a second Trump administration, it will be much easier for political appointees to rig the flow of information and threaten career officials if they don’t align with Trump’s preferences, even if it’s at odds with the scientific consensus. It could impact everything from water to air to workplace and food safety.”

The rationale for the threat to purge the “deep state” is sometimes that the bureaucracy can impede the popularly elected president’s agenda, which has anti-democratic implications. There are reasonable versions of that argument. But as political scientist Francis Fukuyama explains well, a professionalized civil service is a foundational feature of complex contemporary societies. It makes countless day-to-day decisions, and some degree of autonomy is essential to providing the services that we now take for granted as a key feature of modern life. It has all kinds of checks and guarantees of transparency, allowing for this autonomy to unfold while elected leaders make the big decisions. The deliberate suppression or corruption of sound scientific and statistical data, undertaken to rig governing on behalf of elite allies, would not result in something more democratic or more beholden to the people.

Here again, Trump has openly laid out what this would actually look like. At a recent gathering of Big Oil executives, Trump urged them to raise $1 billion for his campaign while dangling a list of specific things sought by the industry that he would give them in return. Trump has also explicitly promised roomfuls of well-heeled donors that he would keep their taxes low while directly soliciting bucketloads of campaign contributions. The large-scale corruption of government information and rulemaking processes would help fulfill his end of such bargains. The result would perhaps resemble a feature of autocratic rule: the selling off of the government for parts to the autocrat’s elite cronies.

Sobering War Games

Back in May and June, a number of high-profile writers and thinkers engaged in a series of tabletop war games to simulate what an unshackled authoritarian president could actually succeed in inflicting on the country. In the simulations—led by journalist Barton Gellman, former Defense Department official Rosa Brooks, and historian Nils Gilman—the “red team” playing the authoritarian president undertook many of the actions that are most frequently warned about. They invoked the Insurrection Act and unleashed the military on protesters, launched prosecutions of Biden and his family, and pardoned all the January 6 insurrectionists.

The results of the simulations were sobering. Those on the “blue team,” who played the roles of Democratic governors, members of Congress, legal advocates, and others, struggled to respond. They poured time and energy into lawsuits that failed to keep pace with the authoritarian president’s designs. The coalition of resistance fractured. It lacked a serious strategy for generating the large, popular, street-level mobilizations that would be necessary to mount mass resistance.

But something else emerged from these sessions. According to participants, intense debate also centered on whether the type of slower-burn authoritarianism discussed above might also pose its own brutal challenges. Brooks suggested the possibility of a scattered piecemeal resistance, in which Trumpian assaults are so diffuse and targets of state persecution are so isolated that it all snowballs on many fronts before anyone knows what is happening. “A slow and steady approach, relying on making examples of selected individuals and organizations, will be less visible, generate far less public backlash, and do as much or more damage,” Brooks told me, adding that the big danger is something that unfolds “little by little, until it’s too late.”

It seems painfully obvious that banking on the law and the procedural checks of liberal democracy during the Trump era has had limited success. The Russia probe found extensive evidence of likely criminal obstruction of justice by Trump, but its final report failed to say so directly or recommend prosecution. Trump’s two impeachments—one for extorting a U.S. ally, the other for fomenting violent insurrection—failed to result in Senate convictions. He successfully enlisted an entire major American political party in the project of rewriting the history of his extensive, serious crimes against the country. Through elite lawyer foot-dragging, enlisting corrupt lower-level judges, and Supreme Court complicity, he has successfully put off federal prosecutions of himself for extremely grave criminal charges. If elected, he will almost surely cancel them entirely.

The law will of course play a critical role in defending the vulnerable from Trump’s most vicious whims. The American Civil Liberties Union, for instance, has drawn up a blueprint delineating plans to combat the persecution of transgender Americans that’s expected in a second Trump administration, such as nixing federal funding to medical institutions that provide any kind of gender-affirming care, which ACLU lawyer James Esseks said “would shut down care for trans people nationwide, adults and youth alike.” The courts and the law will be called upon to rule against illegitimate criminal investigations into enemies of MAGA and prevent them from turning into illegitimate prosecutions, to block the illegal hijacking of National Guards, and to thwart unlawful crackdowns on immigrants, as well as the sabotage of governing processes in the interests of Trump’s cronies.

But another set of solutions might be urgently required here. They call for state-level officials to examine every nook and cranny of their authority and be willing to wield it aggressively against Trumpian abuses. These solutions would have potential targets of persecution restructure their finances and organizations to make them less vulnerable to punitive IRS probes. They entail groups and individuals allying with one another if one is targeted with a corrupt DOJ investigation. As Gellman recently stated, what’s needed are “precommitments” in which all “friends of constitutional government” vow to stick together, come what may. They should exercise their imaginations and full knowledge of the law and governance right now about what might be coming.

In the end, however, there really isn’t all that much of a contingency plan. The only reliable route forward is to thwart Trump from regaining the power necessary to require us to adopt a backup plan in the first place. “The idea is to stop it on the front end,” Walz said, “at the ballot box.”

The media already are self-monitoring. They have been for years. I'm concerned that the "fourth estate" will not only fail badly to call out this insidious methodology, it is, instead, already yielding to it. Is that why the authors don't even mention a role for journalists?